The Concept of Scale

Everything that is well-organized has a starting point, a development, and an end.

Just like every day: we get up, do things, and go to sleep.

Similarly, in a speech, you begin, say what needs to be said, and conclude.

You, right now: you start reading from the introduction (the one you’re reading now), continue with the central part, and then reach the end.

(And then you also subscribe to Patreon to access exclusive resources and support this project! 😜).

Fedele Fenaroli puts it plainly: Music is composed of Consonances and Dissonances.

These two elements, when combined according to specific rules, styles, and the poetic licenses of skilled composers, create the harmonies that we so love to hear!

The composer’s true skill lies in this very ability: learning to manage, shape, and combine consonances and dissonances in the most beautiful and effective way possible.

What is a Scale?

Someone might think that a scale is a succession of something: you have many elements, and you place them one after the other.

True, but incomplete.

The concept of a scale also implies a hierarchy and does not exclude that within it there are subdivisions that have meaning, and that, read individually or in light of a particular context, reveal an alternative meaning they wouldn’t have in another environment.

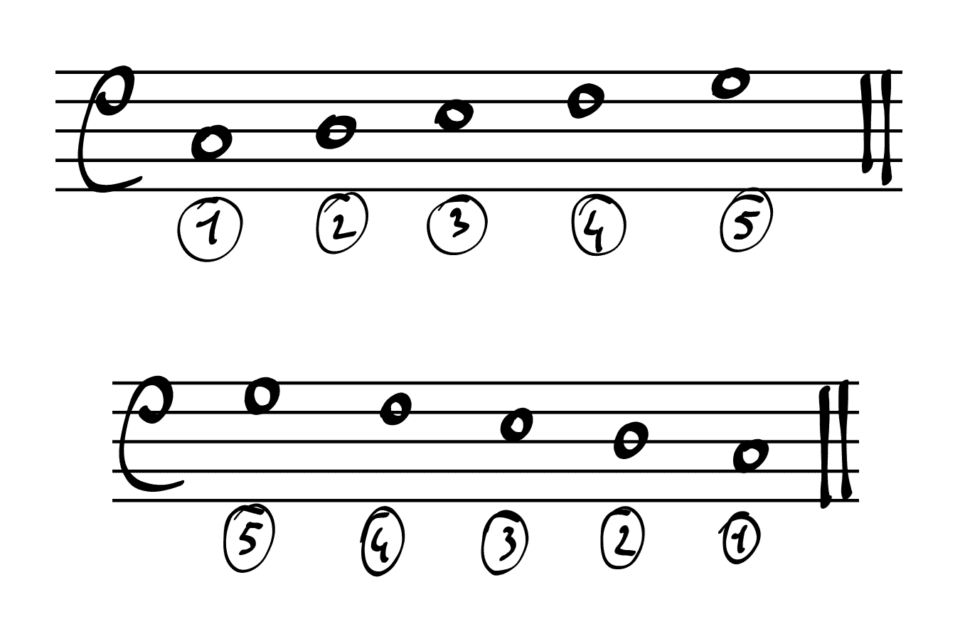

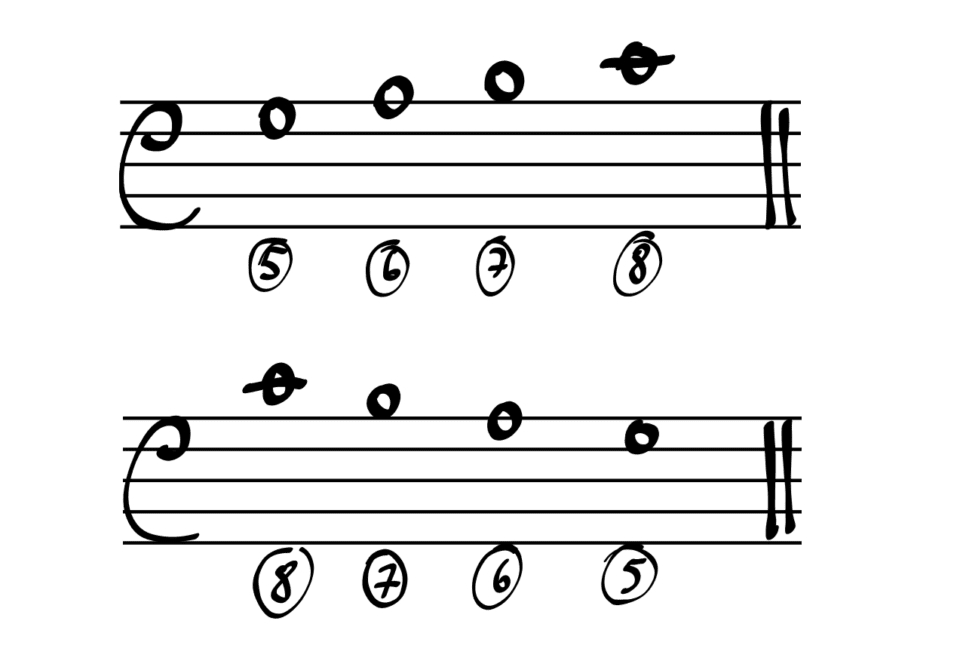

This one you see is a Major Scale, Ascending (which goes up) and Descending (which goes down).

This scale is a succession of 8 notes, grouped into 5+4, a Fifth plus a Fourth.

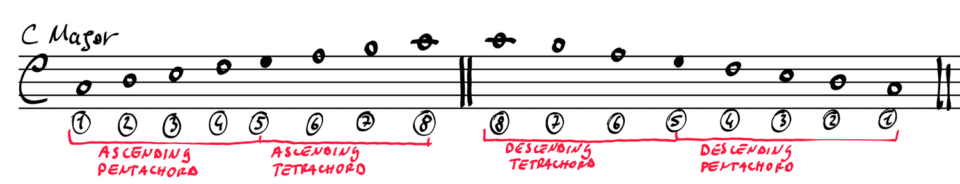

This type of division is very important; the ancients called it the Harmonic division of the Diapason.

The Diapason is the octave and is divided Harmonically when composed of a Fifth plus a Fourth, while it is divided Arithmetically when composed of a Fourth plus a Fifth.

G. Zarlino shows us this in this image from his Istitutioni Harmoniche.

As you can see in this image, the Diapason is the octave, the Diapente is the fifth, and the Diatessaron is the fourth.

This was very important for the creation of the system of the 8 Tones + 1 (In Exitu Israel) and the 12 Modes.

If you want to delve deeper into this topic, you can do so in the Renaissance Musicus Practicus path, where you can learn the Cantus Firmus, the Cantus Figuratus, and the Tones and Modes of the Cantus Firmus and Cantus Figuratus.

If this was very important in the 16th century, it still is in the 18th, but under a different light.

Pentachord and Tetrachord.

Chapter 5 of The Partimento Method, from the Baroque Musicus Practicus path, is entirely dedicated to the study of the Scale from the point of view of its Construction.

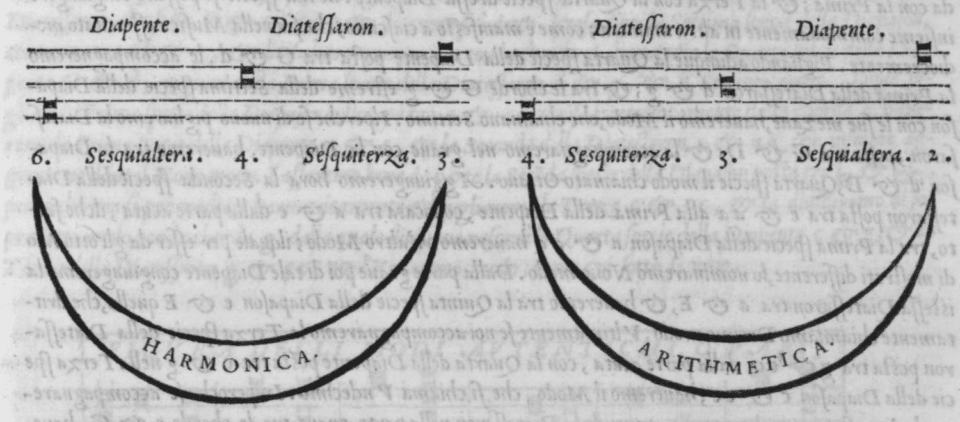

Each scale is indeed formed by a Pentachord and a Tetrachord, which can be Ascending or Descending.

These scales are useful for knowing which harmonies to place in the basso continuo, how to move the voices correctly, and learning some patterns to improvise in the Baroque style.

- The Pentachord is a connection between the first and fifth degrees of a scale.

It can be ascending or descending and implies very different and varied harmonies depending on the context. - The Tetrachord is the connection between the fifth and the eighth degrees of a scale.

This too can be ascending or descending, creating a colorful palette of harmonies and possibilities.

As can be seen clearly, in Tonal Music, the Arithmetical division of the Diapason doesn’t have much significance from a harmonic point of view.

But the Harmonic division, Fifth plus Fourth, assumes significance.

If you want to learn all these things, you can do so in Chapter 5 of The Partimento Method!

You just need to create a free account, start your journey, study, do the exercises, and then continue!

How can they be applied in music?

In this video, Fedele Fenaroli explains how in the Major and Minor Scales, each degree has its function and they don’t all have the same role: some are always “fixed,” while others can change!

Let’s discover it together!